William Bradley of Louth

Slaves in a Caribbean sugar plantation

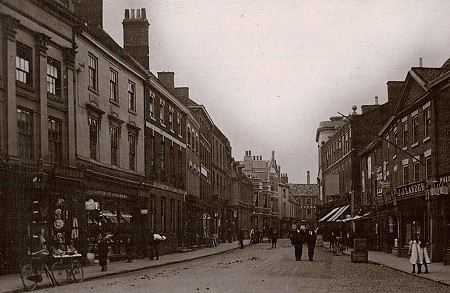

Mercer Row in the early 20th century

Slavery in most parts of the British Empire was abolished by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. The government paid out £20 million in compensation, not to slaves, but to their owners.

Some Lincolnshire connections to slavery are well documented. A specific example is that Thomas Thistlewood from Tupholme moved to Jamaica and treated his slaves brutally. A more general example is that slavery made sugar cheaper, and it became an important part of the British diet.

You may be surprised to hear that the Slave Compensation Commission awarded compensation to William Bradley, a linen draper of Louth, because he was a slave owner. Who was William Bradley, and how did he come to own slaves?

In 1815 William Bradley of Louth married Elizabeth Burnett, and they had four children baptised in St James’ Church. The two boys attended Louth Grammar School from 1826 to 1830. There had been a prominent Bradley family living in Louth in the 16th and 17th centuries, but 19th century linen draper William Bradley, appears to have no close link to these Bradleys.

Now we come to the connection with slavery. The maternal uncle of William Bradley’s wife was Edward Earl of Trelawney in Jamaica, and William was one of the executors and trustees named in Edward Earl's will, proved in 1823. Edward Earl also left William Bradley £500 sterling 'to assist him in his line of business'.

From information in local newspapers and rate books, we have deduced that the shop of linen draper William Bradley was one of the large properties on the southern side of Mercer Row, on the site now occupied by ‘Boyes’. In May 1822 William Bradley had been declared bankrupt. His £500 inheritance from Edward Earl, equivalent to about £62,000 today must have been particularly welcome at this time, and by December 1823, William was back in business, advertising for an assistant to help him in the draper’s shop. But in June 1827, William Bradley’s shop and associated house were put up for sale, and William moved to Legbourne Abbey, which he owned, probably having purchased it with a mortgage when he inherited Edward Earl’s money. Legbourne Abbey too was advertised for sale in 1828 as William was again described as a bankrupt.

William and Elizabeth Bradley, and three of their children seem to disappear from the national records after this – perhaps they moved to Jamaica? Elder son Edward Earl Bradley however remained in England. In 1841 he was in Ingham, which had been his mother’s childhood home and the records of Edward’s daughters’ baptisms tell us that he was a farmer. But by 1851 the family had moved to London, where Edward was working as a ‘cabman’. Edward died in 1857, and his widow Jane became a laundress.

We are left with lots of unanswered questions. Why did William Bradley become bankrupt twice? What happened to William Bradley and his family after 1830? Why were the family of Edward Earl Bradley reduced to poverty?