Poor relief in 1833

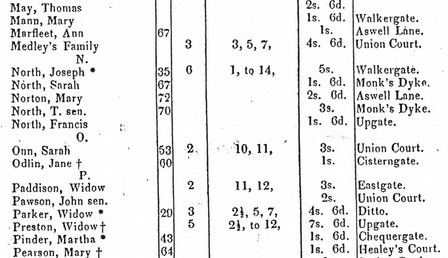

Detail of the list

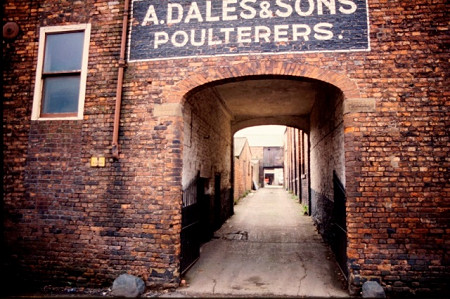

Former poorhouse in Northgate

It was generally a struggle for ordinary working people to survive financially in the early nineteenth century, but when there was no income how did they manage?

In the museum we have a document written by the Overseers of the Poor, entitled ‘Poor Relief for the Parish of Louth 1833’, which lists people who received financial support, where they lived, and (in most cases) their age.

This was when poor relief was the responsibility of the local parish, before the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act established union workhouses. The more prosperous householders had to pay a 'poor rate' or local tax; the funds were used in two main ways. A small number of people who were chronically ill, old, destitute, or who were orphaned children were put into the poorhouse in Northgate (it’s still there, next to the library). Households whose income was too low to support themselves, received money, food and clothes.

In 1833, a total of 349 people in Louth were given financial support – of these, some received only occasional support and some just had their rent paid. The population of Louth at that time was roughly 8,000, meaning that less than 5% received any support. In contrast, today in the UK more than 50% of us live in households that receive more in benefits than we pay in taxes.

The amount given to a single adult living alone was typically 2 or 3 shillings a week. The online inflation calculator tells me that 2 shillings in 1833 would be equivalent to £15 today. This was considerably less than the 10 shillings per week earned by agricultural labourers.

The maximum amount given to anyone was 7 shillings and 6 pence per week. This was for Mrs Mary Preston, a widow who lived in Upgate with her five young children. Her labourer husband George had died in November 1829, at the age of 38. Unlike many other widows with young families, Mary did not remarry. She later worked as a laundress, and she died in 1855 age 57.

Those receiving support were mostly widows with children, or single elderly people. The oldest people in the list are two men - this surprised me as I thought that generally women outlived men - James Spittlehouse age 91 years, and James Keal age 90. Other records tell us that these remarkable men lived to be 95 and 96 respectively.

The recipients of poor relief lived mainly in the less prosperous areas of the town, for example Eastgate (especially Union Court, which is now Priory Road), Walkergate (now Queen Street), James Street, Newmarket, and in the Healey’s Court and Spout Yard area. Many small properties in these areas were demolished in the slum clearance programmes of the twentieth century.