Burial Clubs

Gravestone

Death of Mrs Dimberline

In the early 19th century death rates were high, particularly among children. Without funds, poor families were worried that they might not be able to pay for a funeral, and that family members would be buried in a pauper’s grave along with other bodies, and without a headstone. In response, burial clubs were set up and members paid a regular, usually weekly, subscription. When the time came, funeral expenses were covered, and some clubs also paid out a lump sum.

By the mid-19th century, there were over two hundred burial clubs in Britain. It seemed like a good idea, but soon burial clubs were attracting fraudsters.

The main concern was that these clubs were not subject to any local or government supervision, despite several having up to five thousand members. Inevitably, some clubs collapsed because of mismanagement, accidental or deliberate, and people lost all their subscriptions. In 1817, for example, the House of Commons heard evidence of burial clubs meeting in local public houses and entrusting their subscription money to the publican, who then misspent it.

Some clubs were fraudulent Ponzi schemes which used new subscriptions to pay initial claims, knowing that newer subscribers would never see any payout.

Also, subscribers might abuse the system. If children were unwell and unlikely to survive long, the parents might enrol them in two or three clubs, and on the death all the clubs would pay out, unaware of the duplication. Deliberately provocative pieces appeared in the press, for example one concluding, ‘It is evident that such payments will cover all past charges, even the midwife’s fee; and it becomes a more profitable trade to breed sucking children than pigs or poultry.’

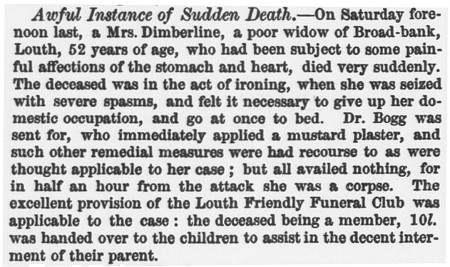

A logical place for burial clubs to develop was in public houses where working men gathered to relax and socialise, and there are references to burial clubs based in Louth pubs. But in 1846, the ‘Louth Friendly Funeral Club’ was set up, the first burial club in the town that was not associated with a pub. It met in the Methodist Schoolroom in Lee Street. A report in 1850, extols the benefits of this club: Mrs Mary Dimberline, a labourer’s widow who lived in Broadbank with her two children, died suddenly and thanks to the ‘excellent provision of the Louth Friendly Funeral Club’, the family was given ten shillings for a decent burial.

In response to national public concern, more formal governance was imposed on burial clubs, including a ban on insuring children under the age of six. Gradually as life assurance policies became more widespread and insurance companies more reputable, the need for burial clubs faded. The last mention I have found of a funeral club in Louth was in 1859.

I thank Julie Bounford for help with this post, and acknowledge input from Susan Grossey, 2025, A grave business, Burial clubs in the nineteenth century, https://regencyinsider.substack.com/p/a-grave-business